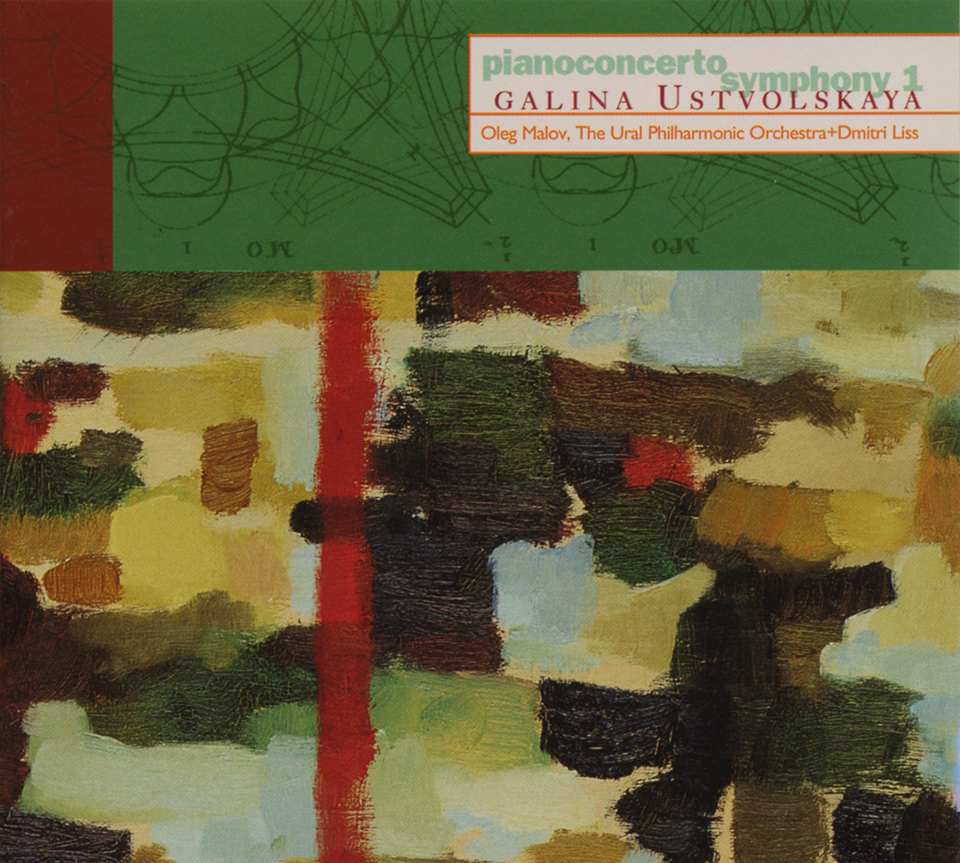

GALINA USTVOLSKAYA

Piano Concerto, Symphony Nr 1

Performer Oleg Malov, Dmitri Liss, Ural Philharmonic

NULLCD MDC 7856 20€ / order

About GALINA USTVOLSKAYA

Piano Concerto, Symphony Nr 1

Galina Ivanovna Ustvolskaya

80 years after her birth in Petrograd – present-day Saint Petersburg – on 17 June 1919, we can safely say that Galina Ivanovna Ustvolskaya is the most ferocious and enigmatic Russian composer of the 20th Century. In 1937, she started her studies at the Professional School for Music in Leningrad and consequently enrolled in courses at the Conservatory. Her education ended abruptly in 1951 after a brief apprenticeship under Shostakovich, as the latter has lost his teacher’s license after his conviction for formalism in the spring of 1948. The influence of Shostakovich, very tangible from 1946 to 1950 (the Piano Concerto, the first two Sonatas for Piano, the Trio and the Octet) was suppressed completely by 1952. From 1947 to the late seventies, Ustvolskaya taught at the Professional School of the Conservatory, albeit without ever being appointed as a professor. She advised some of her students, such as Boris Tchichenko and Viktor Kissine, to write “shorter but more brilliant” compositions. During the first decade following her studies, Ustvolskaya herself composed a number of orchestral compositions during this period: suites entitled Young Pioneers (1950), Children (1952), Sport (1958); symphonic poems such as The Light of the Steppes (1958), The Hero’s Exploit (1959); and also vocal pages, The Dream of Stenka Razin (1948); and choral songs, Hail Youth! (1950), Dawn over the Homeland (1952), Man From A High Hill (1952), Song of Praise (1961). All of these scores met the Russian standards for aesthetics. Nevertheless, they did nothing more than put bread on Ustvolskaya’s table, they did not reflect Ustvolskaya’s very personal, original and unique talent, which had no place in the official life of concerts and musical publications. Unlike the aforementioned pieces, her personal work remained unpublished for many years. The 1952 Sonata for violin and piano, the 1953 Preludes for piano and the 1959 Grand Duo for cello and piano had to wait 15 years for publication. The wait was more than 20 years for the other compositions [Piano Concerto (1946), the first three Sonatas for piano (1947/1952), Trio (1949) and Octet (1950)].

Late recognition

It was not until 1968 that some of Ustvolskaya’s compositions had their premiere in front of a select audience in certain circles in Leningrad. These premieres, however, were not followed by further performances. Consequently, Ustvolskaya’s music remained unknown in Moscow, Warsaw, and the Western countries. The Grand Duo (1968) was probably the first of Ustvolskaya’s compositions to be performed in the West, at the occasion of the 1986 Wiener Festwochen. On 24 June 1988, a new composition, the fourth Symphony Prayer, was performed outside of Leningrad, thanks to Roswitha Sperber and her Institute for Female Composers in Heidelberg, Germany. Even as Gorbachev’s perestroika swept the land, performances were few and far between. In April of 1991, at the occasion of the Spring Festival, pianist Oleg Malov organised a “Composer’s Concert” where some of Ustvolskaya’s work was performed. In 1992, two full-length concerts by the Soloist Ensemble of Saint Galina Petersburg were held respectively in Saint Petersburg and at the Festival of Holland. The conductor on those two occasions was Oleg Malov, Ustvolskaya’s most faithful interpreter of the last quarter century. This second concert marked the beginning of Ustvolskaya’s breakthrough in the West. Over the last decade, the compositions of this catalogue have been performed at the occasion of, among others, the Festival of Huddersfield in Great Britain (1992, 1999), the Zeitflus Cycle of the Salzburg Festival (1997), Wien Modern, the Autumn Festival in Paris (1998) and a Russian Week organised by the Bern Conservatory in 1999. A series of concerts in Belgium, organized by the Gele Zaal (Ghent), in particular with O. Malov and A. Lubimov, have led to these recordings by Megadisc, containing the 21 oeuvres Ustvolskaya selected for the catalogue after the perestroika.

A repertoire of 21+4 oeuvres

The catalogue was published in 1990 by Hanz Sikorski, who is an editor in Hamburg. It contained 21 compositions, a number that was later adjusted to 25 by the addition of 4 less radical scores: The Dream of Stepan Razin (1948), A Suite for orchestra (1955), and two symphonic poems entitled The Lights of the Steppes (1948) and The Exploit of the Hero (1959). These two poems were renamed – rather hypocritically – Symphonic Poems N° 1 and 2, which may cause some confusion because of the aesthetic image that has been attached to Ustvolskaya’s music since the perestroika. This image is based upon the 21 scores that cover all of Ustvolskaya’s creative life, even though they only represent six hours of music. The music in this catalogue bares absolutely no resemblance to the rest of her work. What is more, nothing like it was ever written, not by anyone. These are truly unique pages, written without any compromise whatsoever. They constitute a clean break with musical history, which is confirmed by the composer herself: “There is no link whatsoever between my music and that of any other composer, living or dead. I would like to ask those who truly like it to refrain from all theoretical analysis.” In other words, an actual dialogue with the composer is practically impossible: she turns down all interviews, refuses to be taped or photographed, discourages invitations and trips, and even refuses commissions for new compositions despite the precariousness of her life in Saint Petersburg. “I would gladly write something, but that depends on God, not me”. Ustvolskaya’s God is a rather parsimonious one, as the three homogenous groups that comprise her work only represent two hours of music each: • the oeuvres for piano: a Concerto (1946), Preludes (1953) and six Sonatas (1947-1988) • five pages of chamber music: a Trio (1949), an Octet (1950), a Sonata for violin and piano (1952), two Duos with piano, one for cello (1959), the other for violin (1964) • pages of instrumental music, alternately labelled Compositions (1970-1975) and Symphonies (1955, 1979- 1990), but all of which carry religious titles (with one exception, the First Symphony).

These religious references did not appear until the early 1970s, when Ustvolskaya started composing again after ten years of nearly complete silence. This prolonged sabbatical was caused by the sudden disappearance at the end of 1960 of her love, 37-year-old composer Youri Balkachine. It is therefore very tempting to divide Ustvolskaya’s oeuvre into two very distinct categories: chamber music and instrumental religious music. However, the composer herself tells us that this would be a huge mistake: “My music is certainly not chamber music, even when it is a sonata written for a solo instrument.” She further states that the Latin titles have no liturgical meaning.Ustvolskaya has never written specifically for churches and she does not have the reputation of a practising believer. On that subject, she claims that it is “better to be a decent person than to live the life of a practising believer.” She has a special relationship with the world, with nature (talking to birds and even to ants). Despite her use of titles and texts of Christian inspiration, hers is a distant God whose menacing silence reminds us more of the Old Testament than of the New. It is a god who has a closer relationship to the cosmos than to man’s vale of tears.

Ustvolskaya and Shostakovich

Apart from the official Soviet-type scores and those dating back to the period 1946 – 1950, which we have already discussed, there is a clear distinction between Ustvolskaya’s music and that of Shostakovich. The pivotal composition in this respect is the 1950 Octet, where the pupil radicalises her language with an aggressive keenness. The two compositions on this disc obviously encompass this decisive period in the composer’s life. Ustvolskaya had already turned 27 when she composed the Piano Concerto in 1946, but Shostakovich’s influence is still plainly visible. Ustvolskaya is influenced in particular by Shostakovich’s First Piano Concerto, op.35, with its instrumental colourfulness (piano and strings), sequential movements, octave runs and thematic analogies. The listener may even think he can recognise a motif from the slow movement of the Concerto op.35 and a second one from the coda of the Seventh Symphony, op.60. The composer herself, however, will never confirm this; in recent years, she has adopted an extremely hostile attitude toward every reference to Shostakovich, claiming that he influenced her in a negative way, if at all. In a written declaration published during her visit to Amsterdam in January of 1995, she coldly declared: “At no time, not even when I was still a student, did I feel any affinity whatsoever with either his music or his personality. This supposedly exceptional man is far from exceptional to me. On the contrary, he has ruined my life and has utterly destroyed my most heartfelt feelings”. As if this was not enough, she also questioned Shostakovich’s value as a composer: “I do not believe in those who, like Shostakovich, write hundreds of compositions. Innovation is impossible to perceive in such a flood of work” (1994). The coup de grâce follows in 1999: “I have always found Shostakovich’ music depressing. How could his work ever have been deemed, and I do believe this is still the case today, the work of a genius? His work will pale before time.”

Shostakovich, for his part, has always admired his pupil, both on a musical level (Ustvolskaya and her publisher never failed to exploit his laudative comments) and certainly on a personal level, as it was his desire to marry Ustvolskaya. His personal feelings for the composer obviously led to a humiliating refusal. The 5th Quartet 1953) reflects this crisis through the repeated citations of a motif taken from her Trio (1949). One year prior to his death, this motif was even reprised in the ninth melody, “Night”, of the Michelangelo Suite op.145, clearly a testamentary composition. Time did not fully heal this wound but chose to express it in a different way. Ustvolskaya’s Piano Concerto bears witness to the brief period during which Shostakovich’s influence was still admiringly accepted, even though certain traits already announce the difference between the two composers, such as the kettledrum seconds that are used as a percussive addition and as a dissonant to the sound of the piano. In the new 1998 catalogue, this score is dedicated to Alexis Lubimov, a pianist who was only two when this composition was written. It is, therefore, a dedication a posteriori, a practice Ustvolskaya extends to Reinbert De Leeuw (Composition 1, Dies Irae) and Rostropovitch (Grand Duo). Oleg Malov, however, has fallen into disfavour, even though he was the first and foremost defender of her music, both as a pianist and as a conductor (he participated in eighteen recordings of her oeuvres, five of which were made in Russia before the perestroika!). Ustvolskaya never mentioned him again, even though the score of the 3rd Sonata, which he had already performed, mentions him as the person to whom the composition is dedicated. “The woman with the hammer” wields her tool indiscriminately without seeking advice from anyone, not even from God.

A Strange and Topical Symphony

Despite their titles, Ustvolskaya’s five symphonies (the last four of which can be found on the CD MDC 7854 by Megadisc) are the antithesis of the traditional symphony, particularly when compared to the traditional Russian symphony. The 1st Symphony (1955) is the only one to use a complete orchestral ensemble, but this symphony favours the wind instruments. This composition has a remarkable form. In fact, it is more than likely unique in music history since its two instrumental movements provide the framework for the central vocal part consisting of eight melodies sung by young boys. The texts were written by Gianni Rodari, a militant Italian communist whose finest hour came in Russia during the reign of Stalin (a large collection by Rodari was even published in Georgian). The Russian translations of these eight poems all recount the fate of the poor: the children living in a cave in close vicinity to a dumping ground (N°1, “Ciccio”), the black child that can never know the happiness of white folks (N°2, “Merry-go-round”), the insufficient wages of the father (N°3, “Saturday Night”), the children orphaned by the violent repression of a strike (N°4, “The Youths of Modena”), the rag-and-bone man (N°5), the vagrant in the railway station (N°6, “The Waiting Room”), unemployment (N°7, “When the Chimneys Die”), darkness without hope (N°8, “Sun!”).

This is obviously an ideological comparison between the poverty and misery of the capitalist world and the “glorious sunshine” of Russia. Quite often, Ustvolskaya commemorates this fact through her Suites or Poems dedicated to Russian children, pioneers, heroes and sporting heroes. But the symphony itself did not find favour with the Russian establishment: it was performed only once in Russia,. 11 years after its creation. Apart from the textual contents, the 1st Symphony occupies a unique place in Ustvolskaya’s oeuvre. It is her lengthiest score and it illustrates the evolution of her musical language at a time when she decided to abandon Shostakovich’ post-romantic heritage in favour of an ascetic expressionism more inspired by Stravinsky’s Symphonies for Wind Instruments and his Symphony of Psalms. This is most certainly not a coincidence. In the 1930’s, Shostakovich wrote a transcription for four hands of the Symphony of Psalms for tutoring purposes. The fact that Ustvolskaya was aware of the existence of the transcription has been confirmed by one of her commentaries: “They are weeping psalms”. As in the Symphony of Psalms, the role of the woodwinds and the strings is reduced to accompaniment, which lends the 1st Symphony its own “weeping” atmosphere. It follows that the third movement, which is contrapuntal and purely instrumental, is reminiscent of the start of the fugue of Stravinsky’s second movement. At the same time, Ustvolskaya provides us with something of a social, laic and even political antithesis of Stravinsky’s purely religious approach. Stravinsky’s score even uses the words “composed to the glory of God”. The reverse of a song of praise, Ustvolskaya’s Symphony of lamentations is a private playground for human misery and, worse still, for innocent children, which reminds us of Dostoyevski’s protestation. But fifteen years later, Ustvolskaya bestows an explicitly religious character on these new scores through her choice of Latin titles for the three Compositions (1970/1975), the religious English and German titles for the next three Symphonies (1979/1987) and, finally, the recitation of the Pater in the 5th Symphony “Amen” (1990). Ustvolskaya remains an entirely enigmatic figure, as much by her music as by her attitude and her message. She is the priestess of negation: her music is not chamber music while it does adapt chamber music form, her symphonies are not symphonic, and her music is not religious despite the Latin liturgical titles. She rejects measures and refuses orders. God is the sole accomplice of her decisions and her art. By celebrating her solitude through a music that belongs to no one, and certainly not to music history, Galina Ustvolskaya has erected the pedestal of her own cult, of her own beatification. The two compositions on this disc prove that this was not always the case and, rather paradoxically, the Symphony seems to be the more topical of the two compositions, since the downfall of communism and the triumph of globalisation have certainly not improved the fate of the children of the world.This Symphony dates back to a time when Galina Ustvolskaya wrote from the heart, a time when her hand did not yield yet the hammer that would eventually make her famous. This symphony has only been performed once in the Soviet Union. F r a n s C . L e m a i r e