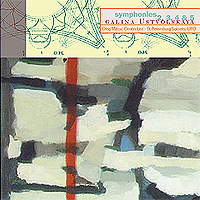

GALINA USTVOLSKAYA

Symphonies 2, 3, 4 & 5

Performer St Petersburg Soloists, Oleg Malov, Dmitri Liss, Ural Philharmonic

NULLCD MDC 7854 20€ / order

About GALINA USTVOLSKAYA

Symphonies 2, 3, 4 & 5

Galina Ivanovna Ustvolskaya 80 years after her birth in Petrograd – present- day Saint Petersburg – on 17 June 1919, we can safely say that Galina Ivanovna Ustvolskaya is the most ferocious and enigmatic Russian composer of the 20th Century. In 1937, she started her studies at the Professional School for Music in Leningrad and consequently enrolled in courses at the Conservatory. Her education ended abruptly in 1951 after a brief apprenticeship under Shostakovich, as the latter has lost his teacher’s license after his conviction for formalism in the spring of 1948. The influence of Shostakovich , very tangible from 1946 to 1950 (the Piano Concerto, the first two Sonatas for Piano, the Trio and the Octet) was suppressed completely by 1952. From 1947 to the late seventies, Ustvolskaya taught at the Professional School of the Conservatory, albeit without ever being appointed as a professor. She advised some of her students, such as Boris Tchichenko and Viktor Kissine, to write “shorter but more brilliant” compositions. Ustvolskaya herself composed a number of orchestral compositions during this period : suites entitled Young Pioneers (1950), Children (1952), Sport (1958); symphonic poems such as The Light of the Steppes (1958), The Hero’s Exploit (1959); and also vocal pages, The Dream of Stenka Razin (1948); and choral songs, Hail Youth! (1950), Dawn over the Homeland (1952), Man From A High Hill (1952), Song of Praise (1961). All of these scores met the Russian standards for aesthetics : they were well-written and beautifully orchestrated. Nevertheless, they did nothing more than put bread on Ustvolskaya’s table, they did not reflect Ustvolskaya’s very personal, original and unique talent, which had no place in the official life of concerts and musical publications. Unlike the aforementioned pieces, her personal work remained unpublished for many years. The 1952 Sonata for violin and piano, the 1953 Preludes for piano and the 1959 Grand Duo for cello and piano had to wait 15 years for publication. The wait was more than 20 years for the other compositions (Trio, 1949 and Octet, 1950). The same need to lead a double life can be witnessed with Shostakovich after 1948, forcing him to divide his attention between docile but well-paid pieces, such as pieces for cinema, and original compositions that were kept concealed for years. Naturally, there is a gap between these two compositional styles but in Ustvolskaya’s case, it would more truthful to speak of a chasm.

Late recognition It was not until 1968 that some of Ustvolskaya’s compositions had their premiere in front of a select audience in certain circles in Leningrad. These premieres, however, were not followed by further performances. Consequently, Ustvolskaya’s music remained unknown in Moscow, Warsaw (for years on end, the local Autumn Festival was the only meeting place between East and West), and the Western countries. The Grand Duo (1968) was probably the first of Ustvolskaya’s compositions to be performed in the West, at the occasion of the 1986 Wiener Festwochen. On 24 June 1988, a new composition, the fourth Symphony Prayer, was performed outside of Leningrad, thanks to Roswitha Sperber and her Institute for Female Composers in Heidelberg, Germany. Even as Gorbachev’s perestroika swept the land, performances were few and far between. In April of 1991, pianist Oleg Malov organized a “Composer’s Concert” in the small auditorium of the Philharmonic Orchestra, at which occasion some of Ustvolskaya’s work was performed. Shortly afterwards, Ustvolskaya wrote a thank-you note to two of the executants, Olga and Jozef Rissin : “I regret to say I am not all-powerful, as I would offer you an island, an old castle or a windmill…”. Is it a coincidence that Ustvolskaya chose images of isolation and solitude to express supreme pleasure? In 1992, two full-length concerts by the Soloist Ensemble of Saint Petersburg were held respectively in Saint Petersburg and at the occasion of the Festival of Holland. The conductor on those two occasions was Oleg Malov, Ustvolskaya’s most faithful interpreter of the last 25 years. This second concert was the beginning of Ustvolskaya’s breakthrough in the West, with concerts at the Festival of Huddersfield in Great Britain (1992, 1999), and at the Festival of the Institute for Female Composers i Conservatory (1999), where the performances of numerous oeuvres (e.g. the complete Sonatas, the second Symphony) were the subject of many lively discussions and comments. n Heidelberg, where during the eight Festival, she was awarded its prize (Ustvolskaya wrote a thank-you note but refused, once more, to leave Leningrad). A series of concerts in Belgium, organized by the Gele Zaal (Ghent), have led to these recordings by Megadisc, containing the 21 oeuvres of Ustvolskaya’s original catalogue. Over the last few years, the compositions of this catalogue have been performed at the occasion of, among others, the Salzburg Festival (1997), Wien Modern, the Autumn Festival in Paris (1998), and a Russian Week organised by the Bern Conservatory (1999), where the performances of numerous oeuvres (e.g. the complete Sonatas, the second Symphony) were the subject of many lively discussions and comments.

A repertoire of 21+4 oeuvres

The catalogue was published in 1990 by Hanz Sikorski, who is an editor in Hamburg. It contained 21 compositions, a number that was later adjusted to 25 by the addition of 4 less radical scores : The Dream of Stepan Razin (1948), A Suite for orchestra (1955), and two symphonic poems entitled The Lights of the Steppes (1948) and The Exploit of the Hero (1959). These two poems were renamed – rather hypocritically – Symphonic Poems N° 1 and 2, which may cause some confusion because of the aesthetic image that has been attached to Ustvolskaya’s music since the perestroika. This image is based upon the 21 scores that cover all of Ustvolskaya’s creative life, even though they only represent six hours of music. The music in this catalogue bares absolutely no resemblance to the rest of her work. What is more, nothing like it was ever written, not by anyone. These are truly unique pages, written without any compromise whatsoever. They constitute a clean break with musical history, which is confirmed by the composer herself : “There is no link whatsoever between my music and that of any other composer, living or dead. I would like to ask those who truly like it to refrain from all theoretical analysis.” In other words, an actual dialogue with the composer is practically impossible : she turns down all interviews, refuses to be taped or photographed, discourages invitations and trips, and even refuses commissions for new compositions despite the precariousness of her life in Saint Petersburg. “I would gladly write something, but that depends on God, not me,” as she told her editor in 1990. Ustvolskaya’s God is a rather parsimonious one, as the three homogenous groups that comprise her work only represent two hours of music each : — the oeuvres for piano : a Concerto (1946), Preludes (1953) and six Sonatas (1947-1988) — five pages of chamber music : a Trio (1949), an Octet (1950), a Sonata for violin and piano (1952), two Duos with piano, one for cello (1959), the other for violin (1964) — pages of instrumental music, alternately labelled Compositions (1970-1975) and Symphonies (1955, 1979-1990), but all of which carry religious titles (with one exception, the First Symphony) These religious references did not appear until the early 1970s, when Ustvolskaya started composing again after ten years of nearly complete silence. This prolonged sabbatical was caused by the sudden disappearance at the end of 1960 of her lover, 37-year-old composer Youri Balkachine. It is therefore very tempting to divide Ustvolskaya’s oeuvre into two very distinct categories : chamber music and instrumental religious music. However, the composer herself tells us that this would be a huge mistake : “My music is certainly not chamber music, even when it is a sonata written for a solo instrument.” She further states that the Latin titles have no liturgical meaning. Fact of the matter is that churches, more than any other setting, do justice to these compositions. She does not add whether this is for acoustic or for other reasons. Her wish was not to be fulfilled in the USSR, where these pieces were performed in an auditorium in 1975 and 1977. Ustvolskaya has never specifically written for churches and she does not have the reputation of a practising believer. On that subject, she claims that it is “better to be a decent person than to live the life of a practising believer.” She has a special relationship with the world, with nature (talking to birds and even to ants). Despite her use of titles and texts of Christian inspiration, her God is reminiscent of the wrathful God of the Old Testament.

Four Symphonies

Each consisting of a single, rather short movement (only the second Symphony is longer than fifteen minutes), instrumentally unusual, using the human voice in a way that is closer to speaking than to singing, these symphonies present themselves as sonorous rituals rather than compositions that are to be performed during a concert. This is confirmed by the instructions on each of the four scores : the role of the performers is detailed right down to the black suit of the narrator-singer and the absence of jewellery for the soprano during the fourth Symphony. The words for the second, third and fourth Symphonies were taken from an anthology of medieval Latin literature, published in Moscow in 1972. Ustvolskaya appears to have been inspired by the strange character of Hermanus Contractus de Reichenau (1013-1054). This Benedictine monk was a paralyzed (hence his name) German nobleman who was renowned for his universal knowledge in diverse fields, ranging from mathematics and astronomy to pietistic poetry and music. Unfortunately, his life was too short to achieve the same level of accomplishment as Hildegard von Bingen. Ustvolskaya manages to mislead us by selecting rather unimportant texts : they do not differ from the trivial litanies that abound in pietistic literature. In the second Symphony, the interjection Gospodin (Lord) and the words Vechnost (eternity) and Istina (truth) are thrice repeated and that is all. The text of the third Symphony Jesus Messiah, save us is a trivial invocation on which there are a thousand variations : “Almighty, True God, Father of Eternal Life, Creator of the World, save us”. The fourth Symphony, entitled Prayer, uses the same text, but the instrumental structure is reduced to the essentials : three musicians instead of 23 for the previous symphony. The fifth Symphony, finally, contents itself with the traditional text of the Lord’s Prayer. In other words, the texts are not the point of interest of these “symphonies” and neither is their influence on the musical discourse. Indeed, the texts are often the very antithesis of the music because of the violence of the musical accents. Most of the time, the words present themselves as a murmured complaint or an insistent supplication, as opposed to the cosmic indifference of the music. The three Compositions dating back to the period between 1970 and 1975 herald a compositional phase during which Ustvolskaya resorted to rather unusual combinations in her choice of instruments (piccolo, tuba and piano in N°1) or even provocative ones (8 contrabasses, piano and percussion in N°2). To a certain extent, Composition N°3 (4 flutes, 4 bassoons and piano) announces the second Symphony (6 flutes, 6 oboes, 6 trumpets, trombone, tuba, piano and percussion). The third Symphony further amplifies the sonorous quest : the groups of five oboes, trumpets and contrabasses are joined by three tubas, a trombone, a percussion group consisting of three large drums and, of course, the piano. Conversely, the fourth Symphony is a veritable about-face, as it is limited to a trumpet, a piano and a tom-tom and only lasts for 8 minutes. The fifth Symphony signals a return to five instruments (oboe, trumpet, tuba, violin and percussion) but, for the first time, the piano is left out. The text is restricted to a free interpretation of the Lord’s Prayer. All of these combinations are fully unique and completely unprecedented in musical history. The groups of 5 or 6 identical instruments permit the formation of clusters, as is standard with sonatas for piano, and there is even that same abundance of diminished seconds, sevenths and ninths. It is salt permanently poured on the wounds of tonal sentimentalism. Fortissimo nuances up to ffffff are dominant, there are numerous crescendos, countered by a total absence of decrescendos, as if the amount of tension can only increase and never lessen. We are reminded of this by the piano and the percussion, that monstrous hourglass of a time that crushes man by its inexorable presence alone. The listener that seeks to discern some human emotion in this music will only find the plaintive sighs of terror and pain. Pity has no place here and this absence of pity would undoubtedly have pleased Nietzsche, who greatly detested Parsifal, the opera of pity and redemption.

One of a kind

When Ustvolskaya declaimed the unique character of her work as compared to the work of “all other composers”, she might have added : “different from any other kind of music, from any other sonorous universe”. A different musical world, in other words, but also a different world altogether. It is not surprising, therefore, that those who have tried to describe Ustvolskaya’s music, like, for example, Boris Tchichenko, do so in cosmological and physical terms : “the sounds and lines run across this music like laser beams capable of slicing through the toughest of metals.” These beams also provide an obstinate, relentless and hammering rhythm, which brings another image to mind. The rhythm reminds Dutch musicologist Elmer Schönberger of a woman wielding the hammer of creation, forging a universe of sound even before the apparition of light. Russian composer Viktor Sousline uses the term “black hole” – found at a huge distance from our galaxy, these stars consist of material of such an enormous density as to imprison their light within their own boundaries . This comparison clearly demonstrates the highly individual character of these obscure and menacing rituals, of this music before musical history, just like a black hole contains light from before the history of light. By using this anti-anthropomorphic compositional method, by dissecting musical history in this particular fashion, the composer from Saint Petersburg has, before the word was even invented, inadvertently written the first postmodern compositions of the 20th Century.

Frans C. Lemaire