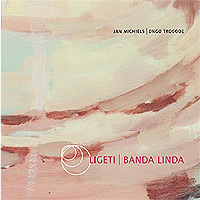

GYORGY LIGETI

First Piano book performed by Jan Michiels - Banda Linda

Performer Jan Michiels, Ongo Trogode

NULLCD MDC 7821 20€ / order

About GYORGY LIGETI

First Piano book performed by Jan Michiels - Banda Linda

DESORDRE !

With reference to his ‘Etudes pour piano’, a work in progress since 1985, composer György Ligeti states : “They behave as growing organisms”. These compositions open up new horizons as they are the product of very diverse spheres of influence. Cases in point would be the work of Frédéric Chopin and Claude Debussy, Conlon Nancarrow’s player piano, geometry as perceived by Benoït Mandelbrot and Heinz-Otto Peitgen, improvisations by Thelonious Monk and Bill Evans, Balcan music, the Balinese gamelan ensembles and Central African polyphony.

On the one hand, the influence of the latter is obvious from the études’ continuous pulsations (that are not bound by a Western metre) and, on the other hand, from the complex asymmetrical organisation of this regular movement. Nevertheless, Ligetis music is not African music !

In 1963, ethnomusicologist Simha Aron discovered the polyphonic ensembles of Central Africa’s Banda Linda tribe. Their music, performed on this recording by the Ongo Trogodé ensemble, is created by an orchestra of ‘trumpets’ and is closely linked to the cult of the forefathers and to burial and initiation rituals. Some of the ‘trumpets’ are extremely large and are shaped from tree trunks or thick branches that have been hollowed out by termites. This creates an artificial duct, allowing the air forced in by the musician’s exhalations to resonate. Simha Aron defines their music as ‘polyphony through polyrhythm’, or sometimes as ‘polyrhythm as a hocket’. The hocket is a technique in which two or more voices exchange a number of fragments of one and the same melodic line – this ‘hoquetus’ writing also featured in our medieval polyphony.

This non-European influence is most noticeable in the opening étude ‘Désordre’; ‘Cordes à vide’ is also reminiscent of a couple of études by Claude Debussy – one of the reasons being that they concentrate on one single interval ; ‘Touches bloquées’ sounds like a hysterically sputtering machine – whereas ‘Fanfares’ presents music emanating ‘from an imaginary island somewhere in between the Balkans, Central Africa and the Caribbean’. ‘Arcen- ciel’ can almost be considered jazz and Ligeti himself refers to ‘Automne à Varsovie’ as a ‘big lamento’ : the archetypically descending and lamenting motif is magnified in a hallucinatory way.

Ligeti had always dreamt of being a great pianist : this goal he never achieved, despite his profound knowledge of the instrument and his passion for the piano repertoire. By his own account, he undertook these études to transform his own pianistic inability into a professionalism of extreme virtuosity – with a wink at the difficulties concerning perspective with the great painter Cézanne, just like Maurits Escher’s impossible perspective is a beautiful metaphor for many of the compositions of the cosmopolitan Hungarian composer. A major enemy of ideologies and systems, he fled Hungary in 1956. He has forged ahead ever since, ‘searching like a blind man in a labyrinth’. He compares the role of the modern composer with the contents of a bubble : physically very small and vulnerable but of infinitely flexible spiritual proportions. This comparison probably also holds true for the position of art in our Western society : the ties with the ritual – the primary pulse of our existence – has been severed almost completely. To the Banda Linda tribe, their music is just as natural as breathing.

The most striking combination on this disc is not a lucrative, trendy crossover : all that glitters is not (dollar) gold. On this disc, you will hear only a fraction of the cultural diversity that surrounds us. The clash between these two worlds reveals a great deal about ourselves and our culture. Is it possible that this creates a fraction of a ritual – as a growing organism ?

JAN MICHIELS