About YASUTAKA HEMMI

Violin Encounters

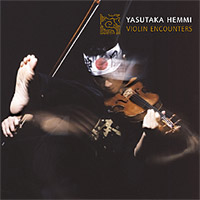

YASUTAKA HEMMI VIOLIN ENCOUNTERS

A variety of inspirations link some or all of this collection. Among compositional preoccupations displayed here, we find a taste for the use of ‘found objects’ (renaissance vocal music, bronze age cave drawings, prerecorded sound and of course the properties of the violin itself), various concepts of polyphony (or rather the constant ambiguity between monody and polyphony which characterises so much writing for the violin), conception in terms of the gifts of a particular performer, and a foreground role for the pure physicality of performance. Of course there is nothing inherently new in this. Early violin works delight in the ability of this flexible instrument to imitate the sounds of nature; subversion of the violin’s typical monodic role goes back to Bach and beyond; and the act of performance as material in itself is perhaps the one link between the folk fiddler and the concert stage. Thus we can see these works in terms not of a continual breaking of new ground but in the context of the violin’s continuing tradition – debatably a more fruitful point of view.

Like most chaconnes, Brian Ferneyhough’s Intermedio alla Ciaccona (1986) is based on a sequence of chords: here the chords number eight, and are shared with many other works in the Carceri d’Invenzione cycle of which the Intermedio forms a part. (Sadly, the cycle still awaits a complete commercial recording.) On the face of it, the Intermedio’s beginning is rather nakedly aggressive. Nevertheless it is explicitly related to the chaconne/ passacaglia tradition, presenting the core material in relatively bare form at the start before elaborating it.

Unsichtbare Farben (1997-98) – like the Intermedio, dedicated to the violinist Irvine Arditti – takes its title from Marcel Duchamp, who used the term ‘invisible colours’ to allude to the contribution of the title to our perception of artworks. Ferneyhough’s own titles (Funérailles, Études Transcendantales, Time and Motion Studies…) themselves often provide an important entrance point for the listener – and indeed for the performer. The work’s material is primarily (but obliquely!) derived from the tenor of Ockeghem’s Missa Caput. The listener might perceive softer harmonies and a more traditional melodic style – stemming not only from the derivation of the material but from changes in Ferneyhough’s own preoccupations in the intervening decade.

As its title implies, Labyrinth X (1997-99) by Keiko Harada travels unpredictably through a range of different musical materials, from a more traditional kind of lyricism to use of the violin’s bare physical properties – with many returns along the way to points previously visited. The range of tone colours specified by Harada is appropriately wide – the violin begins with a metal ‘practice’ mute, as well as employing relatively standard techniques such as pizzicato, col legno and harmonics. Labyrinth X was composed for George van Dam, a co-founder of the Belgian ensemble Ictus.

Like much of David Young’s work, animali (2002) translates visual objects graphically into conventional staff notation. As in other works in Young’s Val Camonica series, these are bronze age rock carvings from the Camonica valley in northern Italy, as transcribed by Emmanuel Anati. Young occasionally leaves them ‘untranslated’, reproducing them directly on the page and requiring the performer to switch between staff and graphic notation. The entire last page indeed consists of the cave drawings superimposed on an otherwise blank musical staff – in a relatively unusual act of compositional humility, Young writes himself out of the piece. Again, animali was conceived with a specific violinist in mind – this time Yasutaka Hemmi. Patrick De Clerck’s Ai Morti (2001) was commissioned by and dedicated to Patricia Kopatchinskaya. Many works conceived for a specific performer embody that performer’s individual manner of playing in the final printed work, and this was indeed De Clerck’s initial intention – finally, however, he elected to allow other performers the same freedoms he had allowed the dedicatee. Rejecting adherence to compositional ‘schools’, De Clerck attempts to “build each oeuvre from the ground up”. Ai Morti takes as an appropriately fundamental starting point two of the violin’s open strings, and all four open strings function as a central reference through much of the work. The composer leaves much to the listener as well as to the performer. Sparse, often ‘white-note’ modal writing suggests (without explicitly defining) a variety of traditions including renaissance polyphony – an effect heightened by the use of the performer’s voice.

In Berio’s Sequenza VIII (1976), composed for Carlo Chiarappa, a mixture of real and implied polyphony is again one of the composer’s stated aims (a common feature of the whole Sequenza series). Like Ferneyhough, Berio makes direct reference to Bach’s Chaconne, although Berio’s core material consists of a mere two notes (appropriately enough, at least in the English musical alphabet, A and B). Again, Berio begins the work with his core material – not only the notes, but the physicality of playing them – at its barest. And like many composers before and after him (not only for the violin), Berio occasionally lets the progression of his material take a back seat to the joy of pure virtuosity.

Michael Maierhof’s Splitting 5 (2000-01), on the other hand, makes relatively few concessions to traditional notions of musical progression. Like Ferneyhough and De Clerck, Maierhof employs musical (or at least sonorous) found objects. The solo violin performs against a pre-recorded CD derived from fragments of aeroplane noise and pop songs (the composer credits Mos Def’s album Black on Both Sides). The aeroplanes become powerfully visceral, while the songs become mechanised – a mediating process completed in the violin part. Indeed the violin itself here functions partly as a found object. It is restricted largely to the display of one of its acoustical properties, being played largely in subharmonics. Harmonics above the ‘normally’ fingered note are of course a staple of violin technique – but when played with higher then normal bow pressure, the violin’s strings can also produce a number of distinct tones below the pitch which would have resulted from conventional playing technique. These sounds are relatively unsusceptible to traditional musical manipulation either by performer or composer, although they are found here in a number of different forms – with different fundamentals, in glissando, or with the violin prepared with a small plastic clothes peg! Their function is thus largely impassive and nondevelopmental, rather like the found objects on the pre-recorded CD – linking them persuasively.

Carl Rosman